HANGING BY A THREAD

After Years Of Rapid Expansion, The Clothing Retail Market Is Facing A Storm Of Change

Fast fashion retailers are flooding the market with cheap wares, fickle shoppers are holding out for discounts and Amazon.com is ramping up its selection. Traditional retailers from Gap to Ralph Lauren are suffering deep losses and closing stores in a struggle to adapt. Who will survive?

MARINA STRAUSS RETAILING REPORTER The Globe and Mail Last updated: Friday, Jul. 08, 2016 7:11PM EDT

As a senior executive at Tiger Capital Group, Bradley Snyder has a bird’s-eye view of the difficulties sweeping through the apparel retail business.

His company does liquidation work. And it has been busier than ever over the past year, helping failed or shrinking retailers sell off fashion goods at discounts and shut hundreds of stores at well-known chains such as Aéropostale Inc., Macy’s Inc. and Danier Leather Inc., among others. His firm of roughly 100 full-time employees has grown, adding new staff in Boston and New York and opening a new office in Santa Monica, Calif.

As a consumer, Mr. Snyder is also part of the problem. He increasingly looks for deals and often finds them online, especially at Amazon.com, the ruthlessly competitive e-commerce giant. He still purchases suits and jackets at tony retailers such as Barneys and Saks Fifth Avenue in New York and Holt Renfrew in Toronto, but he rarely pays full price. Instead, he waits for the items to go on sale – at as much as 60 per cent off.

“If everyone is heading in that direction, it sort of just becomes a discount fair,” said the Boston-based executive managing director of Tiger Capital.

Mr. Snyder of Tiger Capital Group.

After years of rapid expansion, the clothing retail market is being buffeted by a storm of change. The sector is crowded with retailers chasing increasingly fickle consumers. The result is an excess of stores, soft sales and a glut of inventory. That in turn has led to growing pressure on prices and profit margins – a boon for consumers, but tough on retailers struggling to provide solid returns for shareholders. The shifts are squeezing out some weaker players, and shaking up all merchants.

The over saturation in fashion retail comes amid the rise of digital and low-cost rivals that are stealing business from incumbents. By next year, Amazon.com Inc. is expected to become the top clothing retailer in the United States, overtaking Macy’s Inc., analysts at Cowen and Co. have predicted. Amazon has made a big push on its fashion business over the past few years, bulking up on high-end styles and investing in marketing, such as sponsoring the men’s New York fashion week in 2015.

By 2020, Amazon will have nabbed 19 per cent of the total U.S. apparel market, compared with about 7 per cent today, Morgan Stanley analysts estimate. The Amazon Prime rewards program, which provides free shipping among other perks, is fueling the site’s apparel sales, with Prime members 5.5 times more likely to “frequently” purchase clothes from the online retailer, their recent report adds.

Amazon’s share of total U.S. apparel merchandise sales05101520% Projected for 2016 and after Projected for 2016 and after 2015,2016,2017,2018,2019,2020.

https://s3.amazonaws.com/chartprod/W6AvpXMG7t8u6bLT9/thumbnail.png

In Canada, Amazon.ca is catching up. Amazon.ca has added “millions” more fashion items since the launch of its dedicated clothing store in 2012, a spokeswoman said. Its brands include Calvin Klein, Guess, Nautica, Buffalo, French Connection, Kenneth Cole and some private labels, which can generate higher margins.

“It’s tricky out there,” said Richard Deck, president of the Canadian division of apparel titan PVH Corp. of New York, which owns Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger among other brands. “There is just so much choice and everything is accessible ….

“There are just no boundaries for consumers any more. They don’t have to buy at their local shopping centre. There are a lot of options out there for them to shop.”

Added New York retail consultant Michael Gould, former chief executive officer of U.S. chain Bloomingdale’s: “It’s an ocean-change going on out there, not a sea-change.”

The number of store closings, some of them through court restructurings or bankruptcies, keeps mounting. They range from the struggling Gap, Ralph Lauren, Abercrombie & Fitch to the insolvent Aéropostale, Mexx and Jones New York in Canada.

A Gap location on Toronto’s Bloor Street. FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

- U.S.-based Gap Inc., which two decades ago defined casual Friday fashion of khakis and jeans for a generation, has been closing hundreds of stores amid style misses at its Gap and Banana Republic chains. Now even its once-stellar Old Navy discounter is in trouble, with its first-quarter sales down 6 per cent at stores open a year or more. The parent retailer’s first-quarter results reflected a fifth straight quarterly decline in sales and profit. Its stock has tumbled around 50 per cent since the beginning of 2015.

- Aéropostale Inc., a former teen retail idol, filed for bankruptcy protection in May, a victim of fickle consumers who no longer crave logo-driven casual basics. After losing money over the past three years as sales plunged, the chain tried to stem the red ink by closing about a quarter of its stores. Now it’s shutting all 41 of them in Canada and 113 of its 739 U.S. outlets.

- Abercrombie & Fitch Co., once the hot upscale teen destination known for its ads with scantily clad models and logo-studded products, lost its appeal. As it prepares to shut 60 stores this year when their leases expire, it reported a first-quarter loss of almost $40-million (U.S.), its third loss in the last five quarters.

- Luxury fashion icon Ralph Lauren Corp. carries too many products under too many labels and takes too long – 15 months – to develop and get new merchandise to stores, forcing it to discount its products and pinching margins. Now it is shutting almost 100 of its 490 company-owned stores over two years following a few years of sliding sales and profit growth.

- U.S. department store chain Macy’s has also been hit by the onslaught of more nimble competition and consumers’ shifting spending. Macy’s has had to unload unsold products at deep discounts while its key suppliers, such as Michael Kors, increasingly trumpet their own stores. Having recently closed 40 stores, Macy’s reported a first-quarter 5.6-per-cent dip in same-store sales for the fifth straight quarter of decline. Its shares have tumbled around 50 per cent since the beginning of 2015.

- In Canada, apparel retailing has been strained, with festering problems at chains such as Le Chateau Inc. and Reitmans (Canada) Ltd., which closed its Smart Set chain, converting some stores to its other banners. Danier Leather, Mexx and Jacob are among those that collapsed in insolvency court proceedings and shut all or almost all their stores.

A Danier Leather store in downtown Vancouver. BEN NELMS/BLOOMBERG

The pressures have resulted in lower prices and a relentless squeeze on margins. In Canada, apparel prices dropped 9 per cent over the past decade while overall prices rose 16 per cent over that same period, according to industry researcher Trendex North America.

At the same time, the percentage of all items sold on sale in Canada has jumped to 67 per cent of the total $30.2-billion (Canadian) apparel market last year from 55 per cent in 2010, Trendex president Randy Harris estimates.

At major North American fashion chains, total sales-per-square-foot slipped 2.4 per cent to $383 (U.S.) in fiscal 2015, compared with the previous year, according to estimates by retail credit consultancy Creditnall in Great Neck, N.Y.

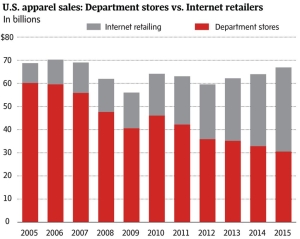

The changes are driven to some extent by consumers becoming more comfortable shopping for apparel online. “Apparel – a business that was long thought to be immune to e-commerce – has been one of the fastest growing online businesses over the past few years and the breakneck pace of growth is expected to continue,” said analyst Daniel Busch at real estate researcher Green Street Advisors in Newport Beach, Calif.

Meanwhile, consumer spending is shifting from buying material goods to such things as eating out and traveling. While travel sales in Canada rose 2.8 per cent to $39.8-billion (Canadian) and restaurant sales grew 4.1 per cent to $54.5-billion in 2015, spending on clothing, footwear and accessories rose only 1.2 per cent to $48.3-billion last year, market research firm Mintel says.

A Holt Renfrew location on Toronto’s Bloor Street. FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Millennials, in their 20s and early 30s, many of whom are strapped for cash, are more likely than older generations to shell out on experiences over possessions, said Carol Wong-Li, a senior analyst at Mintel. “When I’m buying an article of clothing or a purse, it’s really for myself … However, when I’m going out for dinner, yes, I’m still spending money on myself, but there’s that social side of it.”

And some bright spots remain. Consumers still are spending on clothing – they’re just finding new ways and places to buy it. Sales of athletic wear in the United States jumped 14 per cent to $45.7-billion (U.S.) for the year ended May 31, although softer than the 15-per-cent increase a year earlier, researcher NPD Group said.

But as conventional retailers’ inventories build up, the excess merchandise is finding its way into increasingly popular “off-price” discount stores, such as Winners and Saks OFF 5th, contributing to overall moderating prices. At the same time, so-called fast-fashion players, such as Zara of Spain, H&M of Sweden and Uniqlo of Japan, are enticing consumers with cheap-chic styles. They produce fashions sometimes within weeks of the items appearing on designers’ runways, making the traditional nine- to 15-month production cycles of conventional retailers archaic.

“Clearly we need to do more, faster,” Art Peck, CEO of Gap, told analysts in May. “This is an environment that we are operating in today that demands faster change.”

Stefan Larsson, left, and Ralph Lauren, who vacated the top position at his namesake company. CHAD BATKA/NYT

FAST FASHION

It seemed inconceivable even two years ago that Ralph Lauren, founder of his eponymous fashion empire, would step down as CEO and hand the top job to a fast-fashion specialist. But that is what he did last September when Stefan Larsson, former executive at nemesis H&M, replaced him in the top job.

Now Mr. Larsson is overseeing a complete reboot of the Ralph Lauren business, including shortening merchandise production periods to nine months from 15 with eight-week tests. He plans fewer stores, fewer markdowns and fewer products.

“So the world is changing,” Mr. Lauren, still chairman and chief creative officer, told the 49-year-old company’s first Investor Day last month. “Did we drop the ball, did we make some things wrong? Absolutely. Am I happy about it? No. But I believe in this company.”

From PVH’s Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger to Ralph Lauren, the Gap, and women’s wear specialist Chico’s FAS Inc., executives are joining the rush to get inventory onto store shelves faster. Customers demand new styles immediately after seeing them in fashion shows now broadcast on Snapchat, Facebook and YouTube or on the Instagram and Twitter accounts of celebrities.

“It’s probably priority No. 1 for our organization,” said Mr. Deck at PVH, which is shrinking production periods of some items to six from eight months. “The trends come and go so fast now. When it’s on, you want to hit it.”

Shelley Broader, former CEO of Wal-Mart Canada Corp. and now CEO of Chico’s, told analysts recently its focus on improving supply-chain speed is crucial “when you look at not only what’s happening with fast fashion but the immediacy of meeting customer demand.”

Her aim is to cut annual supply chain costs by $30- to $40-million (U.S.) by as early as 2017, she said. “So the idea of changing the cadence of our calendar is that much more” pressing, she added. The chain is trying to respond faster to consumer purchasing patterns by tracking customer data about when shoppers come to the stores, their search for new items and how much they purchase online, she said.

Gap also is moving to tighten its production times. It had hired Mr. Larsson in 2012 from H&M to head its Old Navy discounter, using his H&M know-how to speed product development and deliveries. But by last fall, Mr. Larsson was plucked away by Ralph Lauren.

Still, even some fast-fashion players are beginning to feel the nip of changing times.

Fast Retailing Co. Ltd. of Japan, which is expanding in North America, lowered its financial outlook this spring after price cuts at its star Uniqlo chain hurt quarterly and first-half profit.

In a telling statement in April, CEO Tadashi Yanai criticized his own company for running “bloated operations.” But Mr. Yanai, who is launching the company’s first Uniqlo stores in Canada this fall and, overall, aims to make the chain the world’s largest fashion retailer, has a recovery plan, including cost cuts, more nimble operations and turning around its struggling U.S. division.

At Hennes & Mauritz AB of Sweden, which owns H&M, where second-quarter profit fell 17 per cent as cold weather hurt its spring business and a strong U.S. dollar increased its costs, not everything is fast.

Many of its products are “updated basics” that are produced with relatively long lead times in Asian and other markets, Daniel Kulle, president of H&M North America, said in a recent interview.

He was wearing a crisp white H&M “premium cotton” shirt, priced at $49.99 (Canadian), which took 18 months to bring to stores from the time it was first conceived, he said. H&M updated its “modern classic” shirt from previous styles with a slimmer fit, a thinner “shark” (fanned out) collar and tighter cuffs, he said.

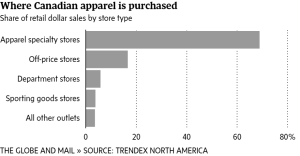

Where Canadian apparel is purchased Share of retail dollar sales in 2015 020406080% All other outlets Sporting goods stores Department stores Off-price stores Apparel specialty stores3.8

https://s3.amazonaws.com/chartprod/f5MS7aMJ2HR6FWy7y/thumbnail.png

Canada’s largest apparel retailers Share of 2015 sales 02468% Reitman’s Gap Lululemon H&M Old Navy Mark’ s The Bay Sears Winners Wal-Mart

https://s3.amazonaws.com/chartprod/6NKWdARaydbvTDaxj/thumbnail.png

TOO MANY STORES

Mr. Snyder of Tiger Capital, which does asset valuations and financing’s for retailers along with liquidations, isn’t surprised at the burgeoning number of store closings. “When I walk the malls, which I do all the time, they’re kind of dead.”

He said many department stores often are empty. “Department stores are just a big warehouse, with inventory sitting there that most days doesn’t get touched … Yet they’re paying for the inventory just sitting there.” Now retailers increasingly use their stores as pick-up depots for e-commerce. But stores are expensive storage spaces compared with Amazon’s warehouses, he noted.

Still, e-commerce can be costly for retailers to develop, requiring investments in technology and, increasingly, free delivery and returns, which eat into margins, he noted.

And when consumers shop online, brick-and-mortar stores get less traffic, which generates fewer “impulse” purchases, PVH’s Mr. Deck said. Impulse purchases can make up as much as two-thirds of a department store’s sales, he said. “You lose some of that online.”

As Ralph Lauren moves to close almost 20 per cent of its company-owned stores over two years, other retailers are making more dramatic moves.

The window display at a Toronto Gap location. FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Gap has been shutting hundreds of stores in North America and now is winding down its Old Navy chain in Japan and looking at closing shops in other markets. “The change that is impacting this industry is obvious,” CEO Mr. Peck said. To underscore the shift to digital efforts, Mr. Peck said the retailer will even reduce its spending on store windows. “If you haven’t won on the digital interface on the front end, your windows in the mall store are probably not going to make a difference,” he said.

Chico’s will shut as many as 175 outlets in all by 2017. “The reports of the death of the retail industry have been greatly exaggerated, but I think we all agree that there is a seismic shift that has occurred,” Chico’s CEO Ms. Broader said. “And retailers need to position themselves correctly to compete in it.”

Still others, such as Aeropostale and American Apparel, have faced worse fates: insolvency and succumbing to bankruptcy or court restructuring.

Jones New York, whose Canadian stores were bought last year by a division of men’s wear retailer Grafton Fraser Inc., filed for court protection from its creditors last month and is closing all its 37 outlets. It had already shut all 127 of its stores south of the border.

Jamie Salter, CEO of Authentic Brands Group of New York, which has since bought Jones New York, said retailers need few stores but the ones they have should be “showrooms” with catchy interactive and other features, which also help to rev up their e-commerce business.

Authentic Brands plans to launch new – but fewer – stores starting next year under its Jones New York and its sweatsuit specialist Juicy Couture brand among others in its portfolio, he said.

Mr. Salter said retailers need fewer stores because Amazon and others have emerged as major e-commerce players and their sales “have to come from somebody. The consumer is still buying. They’re just buying in a different way, from a different place.”

He purchases “pretty much everything online because it’s easier and I don’t have a lot of time.” He buys items such as socks and underwear on Amazon.com with his Prime free-shipping rewards. His wife is the biggest shopper in the family, making many of her purchases online. “Boxes show up at our door every day.”

And while traditional retailers take on Amazon with their own e-commerce, a growing number of them, including PVH’s Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger, have capitulated to Amazon’s sheer might and started to stock their products on its site. Still others, Gap among them, are considering the move. “We are committed to making sure that we are where our customers are,” Gap’s Mr. Peck said. “Amazon’s presence in e-commerce is undeniable in this country.”

Even so, stores still can play a vital role in retail. In the days leading up to Christmas, PVH’s Mr. Deck sends his 50 or so staff at his Canadian head office to retailers such as Hudson’s Bay to help on the floor selling PVH products for three days. He himself serves customers at the Hudson’s Bay flagship store on Toronto’s Queen Street West. His employees do the same for other special occasions, such as Father’s Day.

But he worries about customer loyalty, remembering the days 20 years ago when the Gap and Gap Kids were destination stores for many of his peers. “I’m not sure many Canadians have their go-to store any more.”

Winners accounts for the bulk of discount apparel stores in Canada. FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

PRICE SQUEEZE

Off-price retailers stand out among apparel merchants for their generally strong sales, as stretched consumers head to them for bargains. Chains such as Winners and OFF 5th often sell designer brands for up to 60 per cent off the regular price, stocking goods from prior seasons or, especially now, excess inventory from conventional retailers.

The off-price push is now coming to Canada with a vengeance. Hudson’s Bay Co. is opening up to 25 Off 5th stores in all, Nordstrom Inc. plans to launch its Rack outlets here by 2018 and developers that built luxury outlet malls south of the border – with off-price Ralph Lauren, Michael Kors and other luxury banners – are bringing the malls here, adding to the crowded market.

While retailers such as Nordstrom have struggled with falling sales in their existing traditional U.S. stores, sales at their sister off-price chains have tended to climb. It prompted department-store merchants to introduce more off-price chains: last year Macy’s rolled out Backstage; Kohl’s, Off/Aisle; and HBC-owned Lord & Taylor, Find @ Lord & Taylor.

Still, Jerry Storch, CEO of HBC, which is opening more Saks Fifth Avenue stores in Canada, said it and other retailers plan for lower inventories in the second half of 2016 to ensure they don’t get stuck with unsold merchandise as they did last year. The overstock then needs to be cleared out at discounts, which hurts margins.

Consultant Mr. Gould, however, warned that as retailers scale back inventory levels, they often fail to take risks in choosing merchandise, which results in “boring” offerings.

Amid the squeeze, chains such as Ralph Lauren and Abercrombie & Fitch are aiming to boost margins by touting fewer price markdowns as they focus on fewer, but key, styles.

Still, the stakes are high. “The consumer has been trained to expect discounts,” Mr. Snyder said. “It begs the question: ‘What then happens to the full-price Hudson’s Bay, the new Saks, the new Nordstrom? I don’t know that there are enough shoppers to sustain all of that.”